The British singer-songwriter’s debut establishes a friendly but ultimately passive presence.

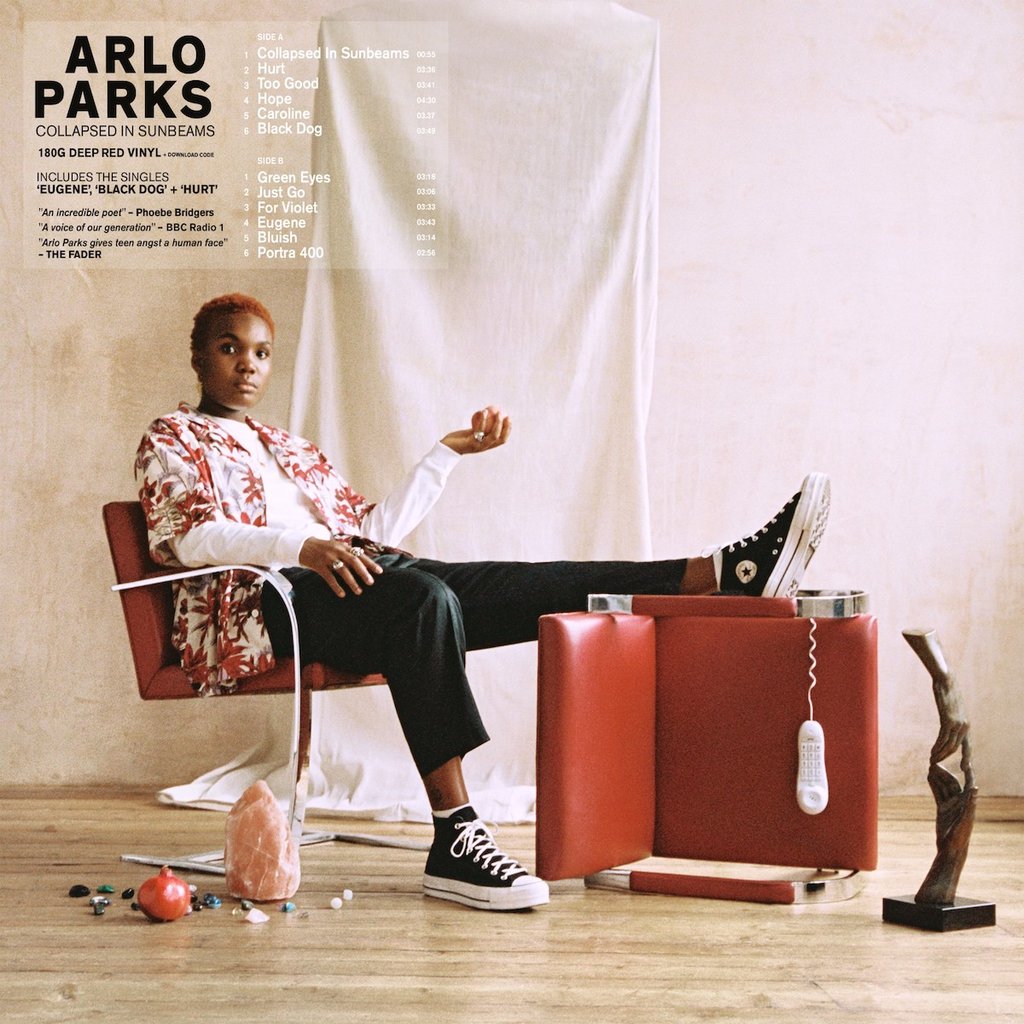

When Arlo Parks made her debut in 2018 with the indie anthem “Cola,” she sang with the tone of a narrator, someone who “didn’t care” but who still had a story worth telling. As she dispensed singles in the two years following, she slowly asserted more control of her narrative lyrically, perhaps nowhere more poignantly than on one of the Best Songs of 2020, “Eugene.” As she recounted each vividly painful memory, she masked her emotions but broke as soon as she confronted the object of her affection in the chorus. Now, with a full record in her name, her songwriting shines, even if not blindingly so.

Parks’ lyricism is front and center on every song, as she plays with each word in her mouth like it’s a whimsical mystery. She opens her debut record with a spoken word poem, making it clear from the first seconds of what will become a part of her musical legacy that she is a lyricist first and foremost, and that should never be forgotten.

And at times, that comes at the expense of the production. While Parks manages to consistently create new, exciting plays on language with her poetry, the instrumentation from the beginning of the album to the end is virtually indiscernible across the different tracks. That feeling of sameness is even more difficult to ignore when Parks repeatedly employs her slam poetry-Esque rhythmic stylings with the same frequency. It’s a mistake that might be interpreted as “cohesion,” but drains the album of some needed color.

The dreamy instrumentation is pleasant but fairs better as background music than as an experience in its own right. But rendering it exclusively such would deprive the listener of some fine details. Perhaps her most interesting artistic ploy on the record was to write two sibling songs, “Caroline” and “Eugene.” Just as likely, though, is that this was unintentional. The chord progressions opening each track are similar enough to draw attention, as she cries out to both in desperation by name, but no other strings tie the two together.

And that highlights by far the greatest oversight of the album: while each of her songs are strong enough to stand on their own, the album doesn’t create a compelling narrative that someone as insightful as Parks would likely be able to create. The tracks don’t speak to each other or build off of one another, leaving the listener without a sense of resolution by the album’s end. Every image she paints is beautifully detailed and styled, but she continues to try to create the same product just with different variables, like swapping names or single instruments.

Arlo Parks is an artist ripe with so much potential, as seen on the album’s strongest tracks like “Hurt” or “Eugene.” But a flawless one she is not, and she succumbs to her humanity as she focuses too much attention on the details instead of seeing the forest for the trees (or the album for the songs).