Embrace the winds of poptimism and shove your Rolling Stones-loving grandpa out the window, Gen Z. Pop is on top.

Everyone has heard the age-old trope that pop music is “trash” or “garbage” at some point in their lives, whether that was referring to The Beatles or Lady Gaga. That line of thinking often stems from the ideology of rockism, the principles that suppose Rock music is a (or the) superior musical genre. While this way of thinking has been Teflon for decades, it has dramatically fallen from universality over the last several years. In its wake, with a rush of minority voices into the fold, comes Poptimism.

Origins

To understand “poptimism,” you have to understand its opposing ideology “rockism,” which first emerged in the 1981 NME article A Race Against Rockism. “Rockism” was instantly a controversial term, one defined roughly defined as the tendency to install rock norms as the critical discursive center, but a term also indelibly linked to racism.[1]Kelefa Sanneh, Major Labels. P. 593-595. Rock music had a decades-long reputation for being to a homogenous boys club of straight white men, one largely segregated from R&B stylings. Who were these men to decide what music was quality?

In the years that followed, different pop and rock groups began rejecting the ideology of “rockism.” But it wasn’t until the publication of Kelefa Sanneh’s article in The New York Times, “The Rap Against Rockism” in 2004 that made Poptimism a legitimate, mainstream school of thought. Sanneh blasted the standard-bearing of rockism in the piece, arguing that pop music is just as worthy of treating as a repository of ideas as rock music. Why should we treat pop songs, which often have more ubiquity and longevity than the “best” rock songs, as being worthless?

While Sanneh helped make the ideology itself mainstream, Poptimism’s big break came around 2002, with the resurgence of Australian pop star Kylie Minogue to the global scene. Minogue was the quintessential pop diva, dominating music markets from the moment her debut single “the Locomotion” dropped in 1987 but shifted sounds with her self-titled LP in 1994. From there, she made a slight left turn for techno and house music before 1997’s Impossible Princess saw her embrace a far more experimental sound. As she slipped from prominence, almost intentionally, she subsequently gained indie cred, most notably after propelling Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds to their biggest hit ever with their duet “Where the Wild Roses Grow.”

When Minogue returned to the world stage with her 2002 album Fever, she released one of the defining pop songs of the decade, and allegedly the catchiest song of all time, “Can’t Get You Out Of My Head.” The album became one of the first Pop records ever reviewed by the infamous Indie publication Pitchfork, who had devoted all of their attention at that point to exclusively reviewing indie and rock music. While the editors have since admitted this was conceived as an April Fool’s joke, notably, the album was given a favorable score of 7.6 out of 10.

Breakthrough

While Kylie Minogue first cracked that poptimist glass ceiling, Swedish pop star Robyn was the one who shattered it with her self-titled record. Robyn had followed a very similar path to Minogue on her way to critical success: her debut record saw international commercial success before conflicts with her label over her musical direction saw her career slump. After two Swedish-only releases on Jive Records, she founded her own label, Konichiwa Records, after being inspired by the indie rock band The Knife. Robyn struck while the iron was hot; with Robyn being released in 2005, she was the perfect candidate to capitalize on poptimism’s newfound legitimacy. The album then became the second pop record reviewed by Pitchfork and landed on its Top 50 Best Albums of 2005.

‘Robyn’ is certainly an excellent record, but it still had plenty of indie rock influences that prevented its acclaim from fully embracing poptimism. The standout single “Be Mine!” originally started as a rock tune similar to the sound of The Knife before being coated in a glossy pop sheen. It wasn’t until Robyn’s follow-up record, the electropop Body Talk, that garnered critical acclaim unlike any Pop album before it. Robyn kept Klas Åhlund on board for the project and brought in former collaborator and the biggest pop songwriter of the millennium, Max Martin.

Although Body Talk’s demos reveal that the songs were also originally conceived with an indie rock sound, the album’s final sound is unabashedly pop, with sharp electronic productions on tracks like “You Should Know Better” and “Fembot.” The LP received an overwhelming critical response, scoring an 86/100 on Metacritic, and landing on decade-end lists for Pitchfork, Esquire, and Consequence of Sound to become one of the most acclaimed albums of the 2010s.[2]According to the Album of the Year’s decade-end aggregate.

Poptimism Today

In Body Talk’s aftermath, Beyoncé‘s self-titled album became one of the first albums by a Popstar ever to garner “Universal Acclaim” on Metacritic, amassing a score of 85 out of 100 in 2013. While it was more of an R&B album than a straight pop one, it made critical acclaim for pop divas a new benchmark for success. Taylor Swift‘s synthpop masterpiece 1989 soon followed in 2014, and Carly Rae Jepsen‘s E•mo•tion trojan-horsed synthpop into Indie circles in 2015. Pop was now being taken as seriously as any other genre.

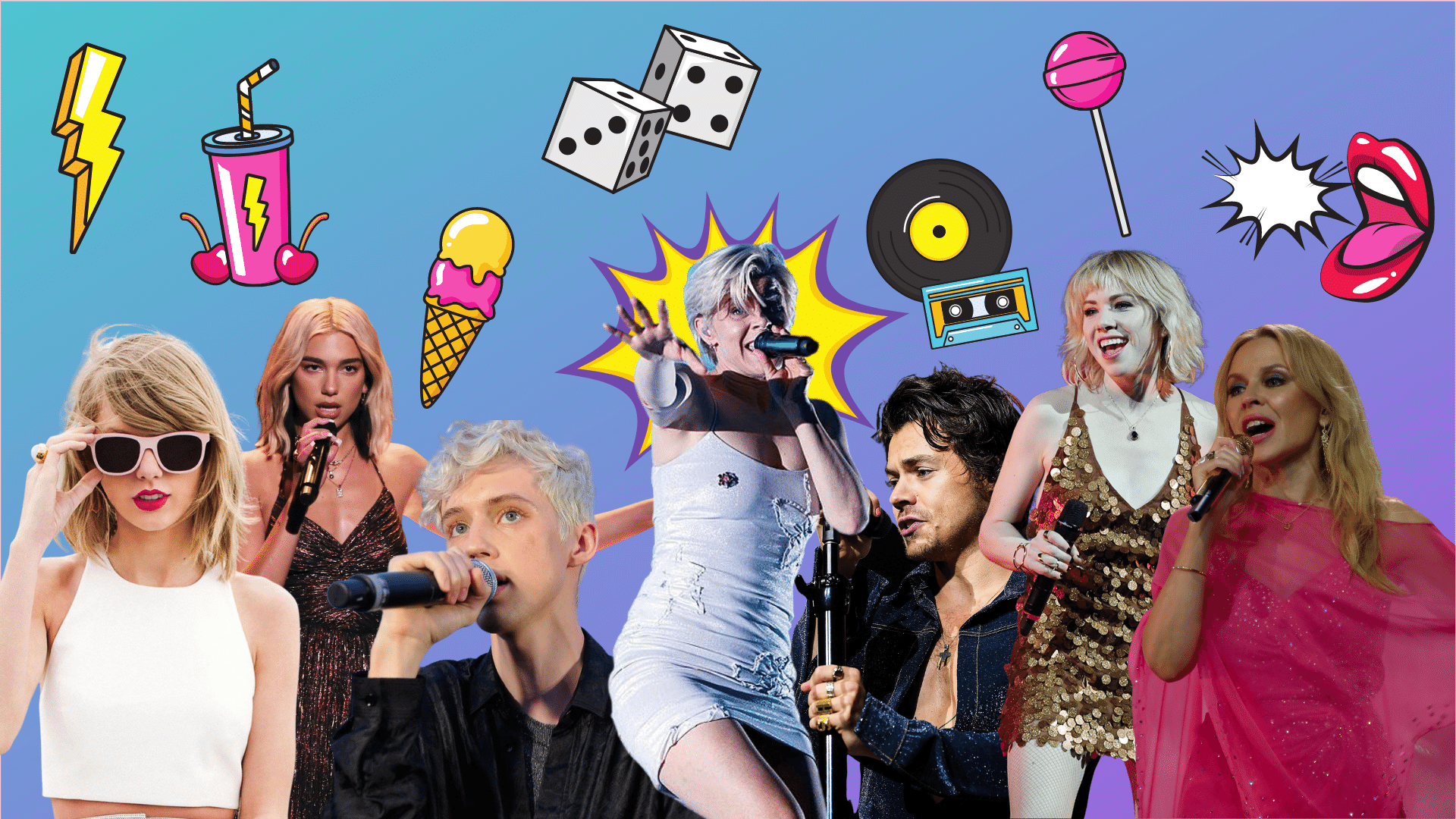

As pop infiltrated the indie scene courtesy of niche artists like Robyn and Carly Rae Jepsen, it became difficult to justify why other pop albums made by superstars without indie cred weren’t worthy of the same respect. Numerous pop projects by bonafide superstars since have cleared the 80-mark on Metacritic and AOTY, including Charli XCX‘s Pop 2 (2017), Troye Sivan‘s Bloom (2018), Ariana Grande‘s Thank U, Next (2019), Dua Lipa‘s Future Nostalgia (2020) and Lady Gaga‘s Chromatica (2020). Now, pop albums can regularly be seen attracting cherished 8/10 scores from various publications. It’s helped push artists like Harry Styles, who makes classic rock-tinged Pop, to critical heights that have typically not been well-received by genre purists.

The people leading this charge have often been minorities, particularly black men and women and gay people. With rock being a genre with a predominately white and male fan and artist base, rockism has historically been dismissive of the musical opinions of other groups. At its worst, it has sought to erase the music of others, like the “Disco Sucks” movement that nearly extinguished the genre as a whole.

But poptimists are by and large more inclusive of other genres and their fans, perhaps most visibly with the relationship between the LGBTQ+ community and women and pop artists, but between other groups as well. Minority voices have attached themselves to the poptimist’s method of evaluating art and music: that women musicians can be – and more often are – just as talented and worthwhile as their male counterparts, and that appealing the lowest common denominator doesn’t instantly preclude art from being considered good. As a truly progressive ideology, it makes sense that it would only thrive in a rapidly progressing and globalizing culture.

The question for music critics, journalists, and fans now isn’t when poptimism will become the predominant lens of evaluation, but rather where the field will progress from here.

This article was initially published on February 19th, 2021. It was republished with additional content on March 18th, 2022.